Hip pain in athletes: clinical overview

This presentation provides a comprehensive overview of hip pain in athletes, reviewing common causes, differential diagnoses, and therapeutic approaches. Through a variety of clinical cases, the specialist illustrates the complexity of this joint and the appropriate treatments depending on the type of injury.

Doctors

Topics

Treatments

Advice

- Dr. Guillaume Muffe

- Hip clinical panorama

- Epidemiology

- Diagnostic approach

- Clinical cases

- Treatments

- Conservative treatment

- Infiltration

- Surgery

- PRP

- Physiotherapy

- Complex anatomy

- Various diagnoses

- Sports load to be adapted

- Useful imagery

- Importance of rest

Information

Video type:

Anatomy:

Why do athletes' hips hurt?

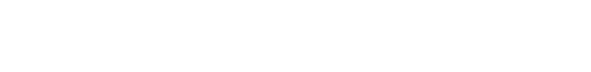

The hip endures high stresses in running, pivot sports, and push-off disciplines. In athletes, pain often stems from a combination of factors: morphology, training overload, repetitive movements, and insufficient recovery. It is not always proportional to the initial imaging.

In this context, the first step is to locate the pain (groin, buttock, lateral face) and its context of appearance (gradual onset, acute point, too rapid return). The anamnesis specifies the load, the volumes, the surfaces practiced and the recent changes in intensity. The objective is not only to name an injury, but to identify the mechanism that maintains it in order to adapt the load and secure the return to the field.

Common Diagnoses and Pitfalls

In young athletes, femoroacetabular impingement is a major generator of groin symptoms. It readily coexists with labral lesions. Gluteus medius tendinopathies and trochanteric bursitis cause lateral and nocturnal pain. Stress fractures of the femoral neck or pelvis should be investigated in cases of mechanical exertional pain. Pubalgia often crosses the hip due to overloading of the anterior chains.

Don't miss: referred pain of lumbar or sacroiliac origin that can mimic coxopathy. The clinical examination compares the mobility of both hips, tests for impingement, gluteal strength, and explores the lumbopelvic chain. The diagnosis is dynamic: it is refined in light of the progress under treatment.

Adapting the sports load is often the key to conservative treatment.

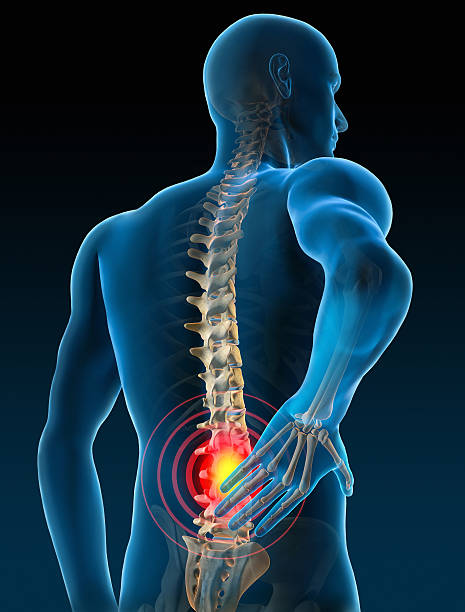

Useful imagery, reasoned imagery

Standard frontal pelvic and hip X-rays remain the basic examination for screening for dysplasia, cam/pincer, and coxarthrosis. MRI and MRI-arthrography can identify labral and cartilage lesions or look for stress fractures. Ultrasound is useful for tendinopathies and bursitis, but its limitations are marked for the deep joint, particularly in very muscular patients.

Imaging does not replace functional examination. It guides the strategy, confirms a hypothesis or eliminates a pitfall. In the event of an atypical evolution, the initial diagnosis must be reevaluated and, if necessary, supplemented.

Conservative treatment: load, motor control and recovery

The majority of hip pain in athletes initially requires conservative management. The focus is twofold: reducing stress (adjusting volumes, surfaces, and cadence) and improving tissue tolerance (strengthening the glutes, lumbopelvic control, targeted mobility). Analgesics/anti-inflammatories can help in the short term. Infiltrations (corticosteroids or even PRP, depending on the context) have a selective role, under guidance, in a comprehensive and time-limited strategy.

Recovery (sleep, periodization, nutrition) is part of the treatment. A gradual, quantified recovery plan allows you to complete each step without experiencing lasting painful awakenings.

One should not hesitate to re-evaluate an initially made diagnosis if the evolution is not favorable.

When to discuss surgery

Surgery is considered in cases of documented failure of conservative treatment, proven mechanical injury, and persistent functional impairment. Arthroscopy corrects impingement, treats a fissured labrum, and smooths selected cartilage lesions. Some dysplasias require reorientation osteotomies. The decision is multidimensional: age, athletic goals, morphology, cartilage condition, and realistic expectations.

The information covers the expected benefits, risks, recovery time and the likelihood of returning to the targeted sport, sometimes with adaptation.

Return to the field and prevention

The recovery follows a common thread: indolence when walking, technical gestures without pain, then reintroduction of constraints (speed, pivot, jumps). The criteria for progression are functional (symmetrical strength, gluteal endurance, dynamic valgus control) and symptomatic (no pain >24–48 h after load).

In the long term, prevention relies on volume management, technical quality, strengthening the gluteal chains, and mobility work. Regular monitoring allows for load adjustments and prevents relapses.

Pathologies treated at the center

Hallux Limitus

Functional

Your pain has a cause.The balance sheet allows us to understand it.

- Gait analysis

- Posture Assessment

- Guidance on the right treatment

- Study of plantar supports and supports

- Detection of compensations

- Pain–movement correlation

The functional assessment allows us to understand how a joint or postural imbalance can trigger or perpetuate pain. Very often, imaging is normal, but movement is disturbed. By analyzing gait, weight-bearing patterns, or posture, we identify the weak links in the chain and guide targeted treatment adapted to the patient's actual mechanics.